17 Ago Nestlé: Five years for a risotto

Solar Impulse, the world’s first attempt to fly around the globe in a solar-powered aircraft, has to stay in Hawaii until spring 2016 due to battery damage during the last Pacific flight. While the plane is fuelled by sun light, the two pilots Bertrand Piccard and André Borschberg also need some “fuel” to survive on the long legs of the flight around the world. Their meals and snacks have been developed over the course of five years by scientists and food experts at the Nestlé Research Center in Lausanne, Switzerland.

6,000 hours of research

Mushroom risotto, potato gratin and curry soup: It might sound ordinary but getting such dishes right took the team of eight Nestlé scientists five years and more than 6,000 hours to research and develop. Led by Dr Amira Kassis, the Nestlé team developed tailored dietary plans and all the food now being consumed by the two pilots seeking to break the world record for solar flight, Bertrand Piccard and André Borschberg.

The challenge lies in feeding them and ensuring they get the nutrition they need at a cruising altitude of 27,000 feet in an unpressurised flight cabin. Both the food and its packaging are specially designed to survive extreme temperatures and varying climatic conditions. It has to be easy to consume, satisfy tight weight constraints and taste good too.

Packaged Nestlé for Solar Impulse 2 flights

Testing new packaging

“There was a lot of trial and error involved. From testing new packaging to testing the food itself to see how it stood up to the conditions,” Dr Kassis said. “Providing the required levels of nutritional quality is of the utmost importance to the pilots, and perfecting all of the various elements took time.”

High altitude often diminishes human appetite, so the pilots’ meals are divided into two main categories. A higher altitude version for consumption above 3,500 metres composed of high energy, high carbohydrate and fatty food items delivered in small portions, and a sub-3,500 metre version comprising higher protein foods in bigger portions.

Assessing nutritional profiles

During their record attempt the pilots are living in cramped, isolated conditions during flights lasting up to six days. Their sleep intervals last around 20 minutes and there is little opportunity for physical exercise. Dr Kassis’ team of physiologists, nutritionists and food scientists began by assessing Piccard and Borschberg’s individual nutritional profiles, including their carbohydrate, fat and protein requirements, and estimating how these would change during the course of a 35,000 kilometre journey comprising 12 flights and 500 hours in the air.

Tests on the pilots conducted at NRC’s metabolic unit assessed, among other things, their energy expenditure. This is a measure of how many calories, including carbohydrates and fat, the human body burns on a daily basis. Nestlé researchers measured each pilot’s muscle mass to work out how much protein to add to their diet. While developing the plans, they also considered the harsh physical conditions that the pilots would endure, including sharp changes in temperature and altitude.

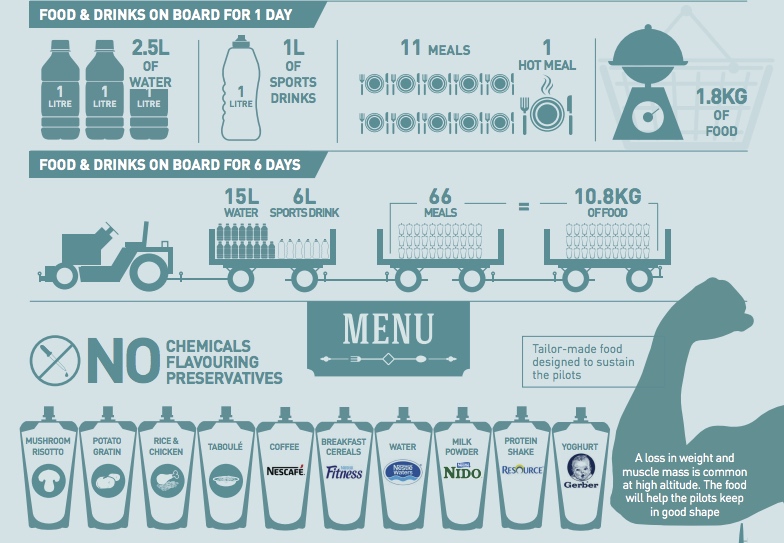

How much does a “solar pilot” need in 24 hours?

Tailor-made menus

Dr Kassis and her team used this data to help them create a menu of 11 different meals and snacks tailor-made for each pilot, which they then tested via flight simulations with Piccard and Borschberg in 2012 and 2013. These tests measured factors including the pilots’ food intake, pre- and post-flight body weight and protein balance. The NRC team used the results to better tailor the meals to in-flight conditions, and ran taste tests with the pilots to get more information on their food preferences.

“Working with the pilots, we discovered, of course, that they have different preferences. For example, one prefers vegetarian options while the other dislikes chocolate,” Dr Kassis said. “The aim of the tasting sessions and agreeing menus with the pilots was important to ensure that they would actually eat the food in an environment where their appetite might not be the same as usual,” she added.

Solar Impulse 2 pilot André Borschberg enjoying a Nestlé meal during flight

Critical food weight

Storing and serving the food was the other big challenge. Despite having a wingspan larger than a Boeing 747, the Solar Impulse plane is only about as heavy as a family car, which meant the Nestlé researchers had to carefully consider the weight of all food and drink taken on board, including the packaging.

The total amount of food per flight cannot exceed 2.4 kilograms, and the volume of liquid allowed cannot exceed 3.5 litres (2.5 litres of water and 1 litre of sports drink). Ease of use is vital, so packaging includes pouches for soups and drinks that limit the risk of spillage, and ‘flexi cups’ that turn into cups once opened. A specially designed self-heating bag is used to heat up food contained in pouches.

No artificial preservatives

To preserve the food effectively, the Nestlé team developed a process whereby uncooked food ingredients are put into special packaging and then heat treated. This process seals in the freshness of the food and helps maintain its texture, preserving it for up to three months without the need for artificial preservatives.

In addition to being easy to use and lightweight, packaging has been physically tested to cope with fluctuations in air pressure. After Solar Impulse completes its journey, Nestlé will consider how to apply the knowledge it has learned, which could be used to develop nutritional programs for high-altitude sports and expeditions.

Text and photos: SCCIJ with material of Nestlé.